コラム

落合憲弘

John Sypal

タカザワケンジ

なぎら健壱

In general, most people take family snapshots in the belief that they’ll last forever- so that the loved ones and the moments caught within will be preserved for their future.

What then, when the picture outlives the subject?

When does the fear of forgetting outweigh the pain of remembering?

Yachio Enomoto didn’t set out to become a photographic artist.

The pictures she took of her son, Yuto, were much like the millions of similar snapshots taken of around the world every day. Namely, pictures created not with lofty artistic intent but with a clearer, truer vision: The shape of love that new parents, enamored by preciousness of their child, possess. Such photographs might not mean much to strangers, but they mean everything to those found in them.

We all recognize the rhythm of a typical family photo album. It begins with the birth of a child, and continues, punctuated by milestones and memories, page after page along the flow of time. This expectation is so standard that -despite common sense and tragic news reports- pondering any other possibility is simply unthinkable.

And yet, on August 10, 2005, through a tragic, unimaginable accident, Yachio Enomoto and her husband were confronted with the loss of their only child.

In the years that followed she remained engulfed by the trauma of her grief. This grief for her son -and for the future that would never come- kept her from revisiting the images of their past. Over time something heavy and suffocating welled up inside. Confrontation was inevitable. Unexpectedly, the key to its release- to her release- was an encounter with photography at age 47.

At her exhibition “ Family Photo” held at Roonee 247 Fine Art this August, Enomoto told me that it was Miyako Ishiuchi’s images of clothing and personal items of Hiroshima’s atomic bombing victims that sparked her own photographic journey. Ishiuchi’s straightly-presented works suggested human loss could be addressed and even transformed through photography. She realized then that she didn’t have to search far to take photographs- everything she needed was, in a sense, already there. Upon realization that seemingly unforgettable moments were beginning to fade from her memory, photography could provide proof that her son had lived- and was loved.

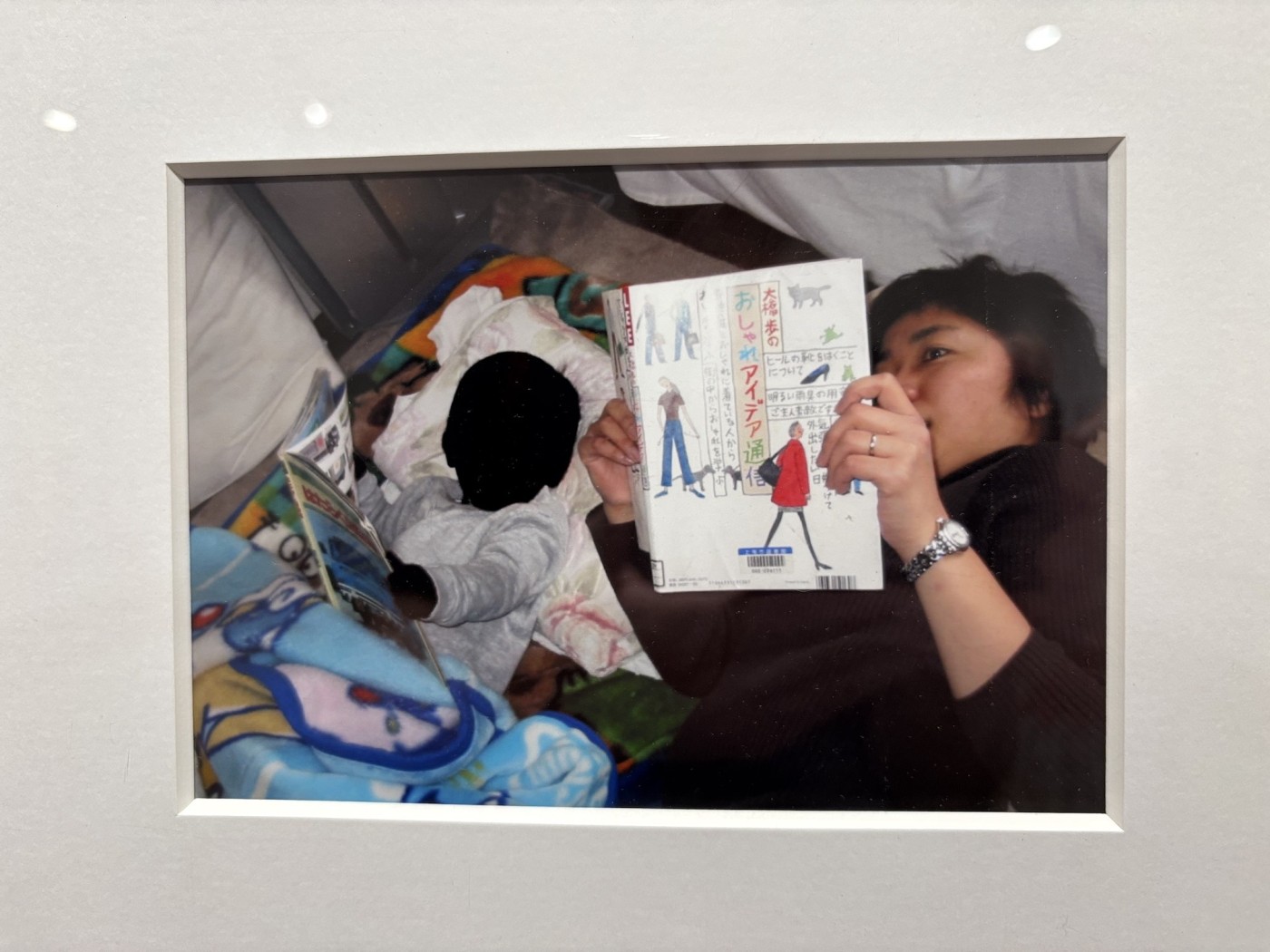

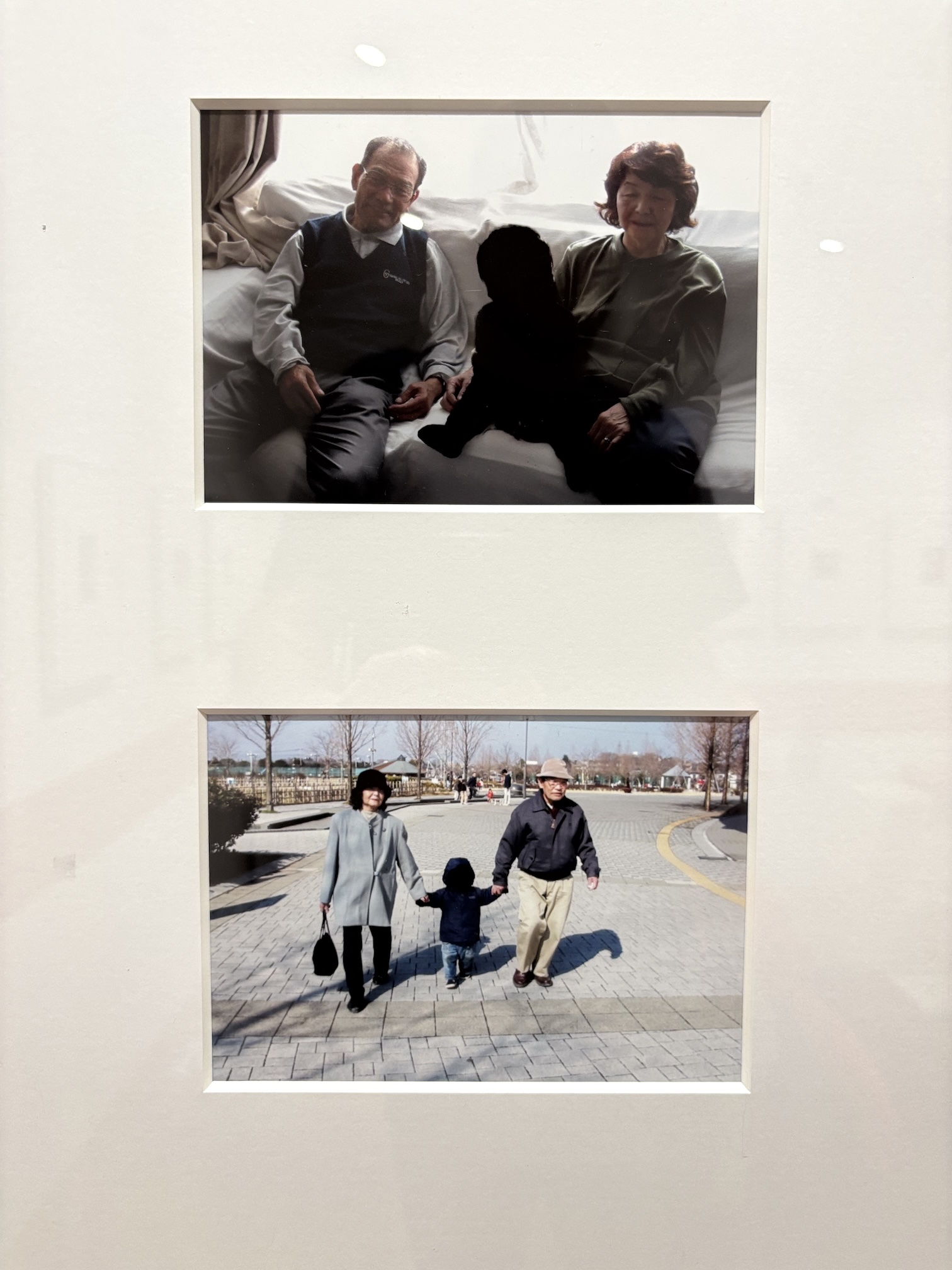

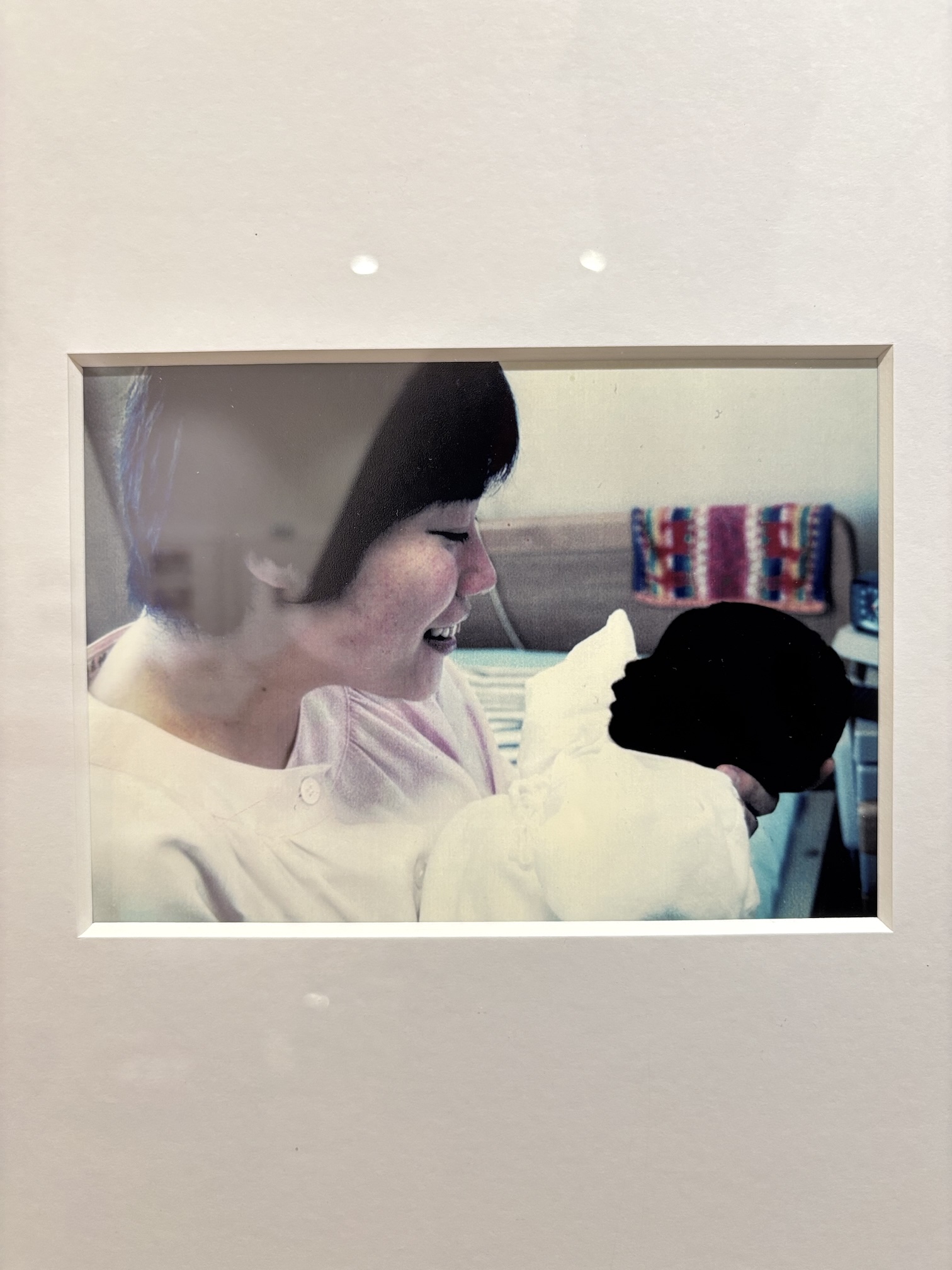

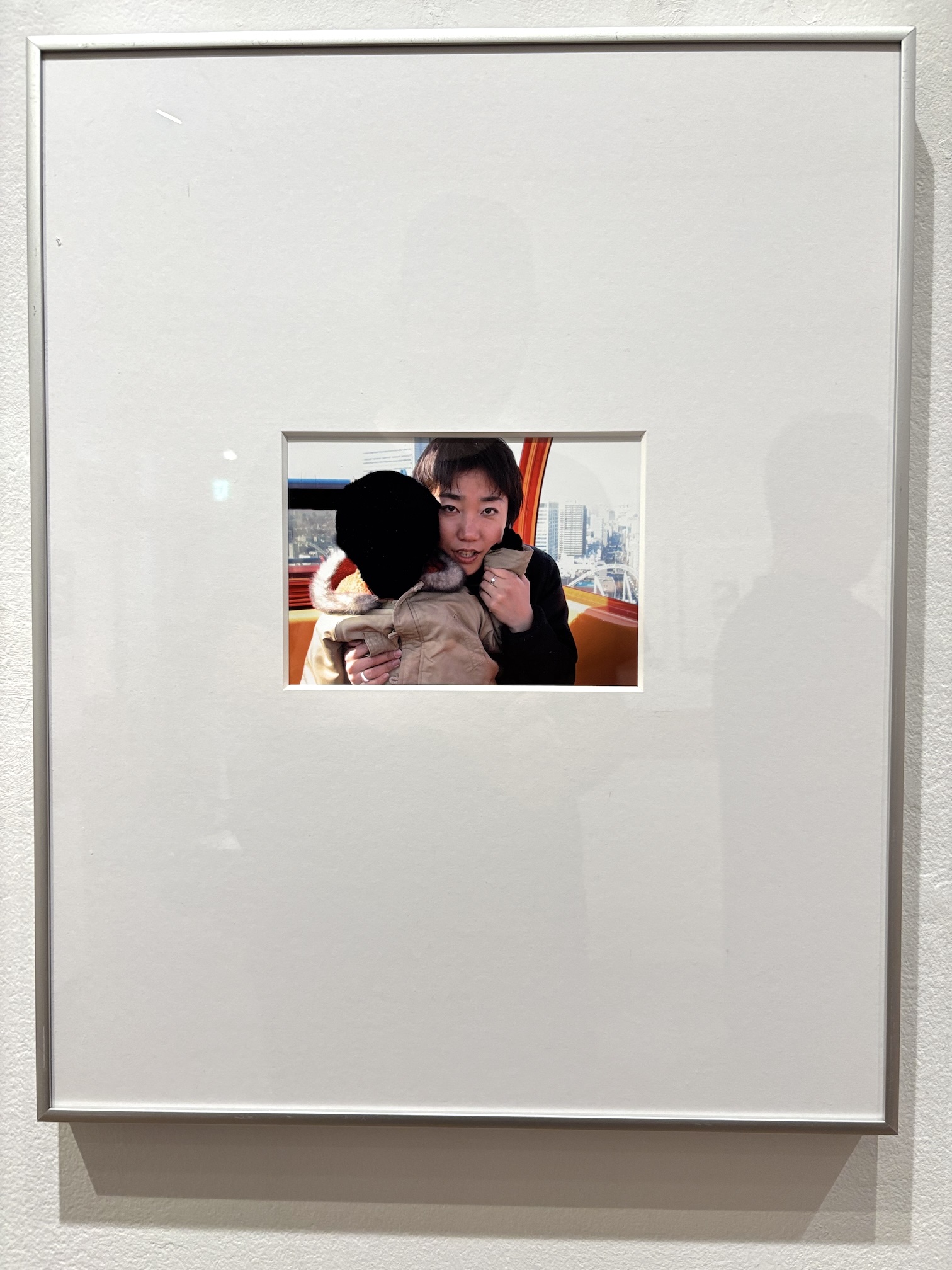

So, through unimaginable pain and admirable, unimaginable bravery, Enomoto reopened her family photos. Smiling in the pictures, her son and their future together were still there. Here he is sitting in her arms as a newborn, later holding hands together on trips to parks, or sharing book time in bed. There he is, hand in hand with grandpa and grandma, or in her arms commemorating a trip on the bullet train. Photographs like these are universal- and yet, for through grief, painfully specific.

For Enomoto, these pictures led to reflection on the nature of existence- and its relationship to photography.

In her statement she writes:

"If someone disappears from a family photograph, does that mean they never existed?

I wondered about this. If photographs are the only way to hold to memories as they fade over time, I wanted to see how the meaning of these "family photographs" would change for me if those who are gone were to disappear from the photographs”

“To disappear”.

From her album she scanned her family photos. Facing her computer monitor, in each one she carefully blackened-out her son. The inky, child-shaped form in each is not simply a surface obfuscation but the revelation of an utterly silent void. Enomoto told me that the blackness is not a surface, but rather the metaphoric “hole” into which he fell.

The black hole through which he was pulled.

" There is a 'black hole' in the photograph. He is no longer there. He fell through that hole. And it feels as though his "memories" and "recollections" are slipping away from my memory, and it also feels as though my memory is mobilizing to fill in the gaps and prevent this. I'm curious to see where this hole leads."

The repetition of the jet-black child both connected the pictures visually and, with his absence, with a weight of loss. In the prints these black shapes also contrasted against the typically vibrant hues of amateur snapshots, here prints presented slightly larger than the one-hour ones typically found in a family album. Each photograph—or sometimes in a grouping of up to three—was presented in a silver frame in Room 1 of Roonee.

The gallery space itself, is roughly the size and shape of an ordinary living room. Enomoto had reinforced the sense of domesticity by including a small sofa, coffee table, bookshelf, and other casual furnishings. Scattered throughout were children’s books, stuffed animals, toy trains, and action figures. Running just below the row of photographs was a strip of deep-orange paper, taped at child’s height along the walls. On it, stickers of cartoon characters and animals had been haphazardly arranged, further evoking the textures of everyday family life. Rather than creating a sense of lightheartedness, this familiar home-like environment intensified the emotional impact of the work. One can imagine that the show’s impact would differ between men, women, parents, children- and especially mothers. While I have no children of my own, stepping over discarded action figures and weaving around stuffed animals to view images such as these was an experience more affecting than anything I had experienced in a gallery before.

Enomoto told me that this exhibition was not intended as a memorial to her son, but a way of inviting viewers to reflect on how such a loss might alter their own lives. Rather than simply a meditation on a single death, this exhibition was a catalyst to stir in the heart a renewed recognition of the fragility and value of life – and perhaps family photography- itself.

一般的に、人々は家族写真を「永遠に残るもの」と信じて撮ります。愛する人々やその瞬間を未来に保存するためです。

では、写真が被写体よりも長く生き続けたらどうなるのでしょうか。忘れることへの恐怖が、思い出す痛みを上回るのはどんな時でしょうか。

榎本八千代さんは、最初から写真家を目指していたわけではありません。彼女が息子の侑人さんを撮った写真は、世界中で毎日のように撮られる何百万ものスナップ写真と同じものでした。つまり、崇高な芸術的意図ではなく、新米の親が愛する我が子の尊さに心を奪われたそのままの視線で撮られた、真実の形の写真です。こうした写真は他人にはさほど意味を持たないかもしれませんが、写されている本人や家族にとっては全てを意味します。

私たちは、典型的な家族アルバムのリズムを誰もが知っています。子どもの誕生から始まり、節目や思い出に彩られながら、時間の流れに沿ってページがめくられていきます。この期待はあまりに当たり前で、常識や悲劇的なニュースがあっても、別の可能性を考えることなど想像もできません。

しかし、2005年8月10日、榎本八千代さんと夫は、想像を絶する事故によって、唯一の子どもを失うという現実に直面しました。その後何年も、彼女は深い悲しみに包まれました。息子への悲嘆、そして来ることのなかった未来への悲しみは、過去の写真を見返すことを彼女から遠ざけました。やがて、心の中に重く息苦しいものが積もり、向き合わざるを得ない時が訪れます。意外にも、その解放の鍵となったのは、47歳で出会った写真でした。

今年8月にRoonee 247 Fine Artで開催された個展「家族写真 / Family Photo」で、榎本さんは語ってくれました。自身の写真の旅を始めるきっかけとなったのは、石内都さんの広島原爆被害者の衣服や遺品の写真だったとい。石内さんの作品は、失われた人々の存在を写真で表現し、変換することができることを示していました。榎本はその時、自分が遠くへ探しに行く必要はなく、必要なものはすでに身近にあることに気づきます。消えつつあるかに思える記憶を写真が証明してくれる——息子が生き、愛されていたことを示すことができる——と。

想像を絶する痛みと、並外れた勇気を経て、榎本さんは家族写真を再び手に取りました。写真の中で微笑む息子と二人の未来はそこにありました。新生児として腕に抱かれる姿、公園で手をつなぐ姿、寝室で本を読む姿。祖父母と手をつなぐ姿、新幹線の旅を記念して抱かれる姿。こうした写真は普遍的でありながら、悲しみによって痛烈に個人的でもあります。

榎本さんにとって、これらの写真は存在の意味、そして写真との関係について考えさせるものでした。彼女はステートメントで次のように書いています。

- 家族写真からその姿が消えたとしたら、その人は存在してなかった事になるのだろうか?と疑問を持ちました。記憶が時間と共に薄れていく中で、写真が記憶を繋ぎ止めておける唯一の手段だとしたら、写真からその存在が消える事により、これらの「家族写真」の存在意味は自分にとって、どう変化していくのか確認してみたいと考えたからです。

「その存在が消える」ということ。

彼女はアルバムから家族写真をスキャンし、モニターに向かい、ひとつひとつ慎重に息子の姿を黒く塗りつぶしました。そのインクで描かれた子どもの形は、単なる表面の隠蔽ではなく、完全に静かな空虚の表れです。榎本さんによれば、この黒さは表面ではなく、彼が落ちた比喩的な「穴」です。彼が吸い込まれた黒い穴です。

- 写真には「黒い穴」が開いてます。彼の姿はありません。彼はその穴から落ちてしまいました。そしてそこから彼の「思い出」や「記憶」も私の記憶から抜け落ちていくような気もしますし、それを防ぐために私の記憶が総動員して補填してる気もします。そしてこの穴はどこへ繋がっていくのか興味があります。

黒く塗りつぶされたの子どもの形の反復は、写真を視覚的に繋げると同時に、彼の不在という喪失の重さを示しています。プリントでは、この黒い形がアマチュアのスナップ写真に見られる鮮やかな色彩と対比され、家族アルバムにある1時間プリントよりやや大きめのサイズで展示されていました。それぞれの写真、あるいは最大3枚でまとめられ、銀色の額に収められています。

ギャラリースペース自体は、一般的な居間ほどの広さと形をしています。榎本さんは、小さなソファ、コーヒーテーブル、本棚などの家具を置き、家庭的な雰囲気を強調しました。子どもの本、ぬいぐるみ、汽車のおもちゃ、アクションフィギュアが散らばっています。写真の列のすぐ下には、子どもの目線の高さに沿って深いオレンジ色の紙が貼られ、キャラクターや動物のシールが無造作に貼られていました。日常の家族生活のテクスチャーをさらに感じさせる演出です。

この家庭的な環境は、軽やかさというよりも、作品の感情的なインパクトを増幅させました。男性、女性、親、子ども、そして特に母親によって、この展示の受け取り方は異なるでしょう。私自身は子どもはいませんが、散乱したフィギュアをまたぎ、ぬいぐるみの間を縫うようにして写真を見る体験は、これまでギャラリーで経験したことのないほど心を揺さぶられるものでした。

榎本さんは、この展示が息子の追悼を意図したものではなく、観る者に「もし自分の人生から大切な存在が失われたらどうなるか」を考えさせるためのものであると語ってくれました。単なる一つの死を巡る瞑想ではなく、この展示は心に「命のはかなさ」と「命の尊さ」、そしておそらく「家族写真そのもの」の価値を改めて認識させる触媒となっているのです。

- 榎本八千代 / Yachio Enomoto

- 「家族写真 / Family Photo」

- 会期:2025年8月21日(木)〜8月31日(日)

- 会場:Roonee 247 Fine Arts

- https://www.roonee.jp/exhibition/room1/20250718161104

Vol.43 Azamino Photo Annual 2026 Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino 20th Anniversary Exhibition : Mr. Naylor’s Wunderkammer あざみ野フォト・アニュアル2026 開館20周年記念 横浜市所蔵カメラ・写真コレクション展「Mr.ネイラーの驚異の部屋」

2026/02/06

Vol.43 Azamino Photo Annual 2026 Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino 20th Anniversary Exhibition : Mr. Naylor’s Wunderkammer あざみ野フォト・アニュアル2026 開館20周年記念 横浜市所蔵カメラ・写真コレクション展「Mr.ネイラーの驚異の部屋」

2026/02/06

Vol.42 Werner Bischof at Leica Gallery Tokyo, Omotesando and Kyoto ワーナー・ビショフ写真展(ライカギャラリー東京、表参道、京都)

2026/01/31

Vol.42 Werner Bischof at Leica Gallery Tokyo, Omotesando and Kyoto ワーナー・ビショフ写真展(ライカギャラリー東京、表参道、京都)

2026/01/31

Vol.41 中嶋琉平|Ryuhei Nakashima「Asia, New York, and Tokyo」、高地二郎|Jiro Kochi「GINZA: Through the eye of a Salaryman 1950-1990」

2025/11/08

Vol.41 中嶋琉平|Ryuhei Nakashima「Asia, New York, and Tokyo」、高地二郎|Jiro Kochi「GINZA: Through the eye of a Salaryman 1950-1990」

2025/11/08

PCT Membersは、Photo & Culture, Tokyoのウェブ会員制度です。

ご登録いただくと、最新の記事更新情報・ニュースをメールマガジンでお届け、また会員限定の読者プレゼントなども実施します。

今後はさらにサービスの拡充をはかり、より魅力的でお得な内容をご提供していく予定です。

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け 書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント

書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント