コラム

落合憲弘

John Sypal

タカザワケンジ

なぎら健壱

In turbulent late 1930s, two young men from Tokyo's Shitaya (now Taito) ward, Hiroshi Hamaya and Kineo Kuwabara, roamed the city snapping photographs as they liked. This was not a common nor affordable hobby at the time but in Hamaya’s case, he was by then already working as a freelance photographer. Kineo Kuwabara, two years older than Hamaya, had the family business, a pawn shop, which provided him the means necessary for his photographic habits. (It is said that a Leica at that time cost as much as house.)

After the war, Hamaya made a career as a photojournalist, and in 1960, became the first Japanese photographer to join Magnum Photos. His work on Japan’s mountain village culture and folklore is an essential part of the Japanese photographic canon.

For the most part, as it was thought, Kuwabara’s photographic interest shifted to the discovery and encouragement of emerging talent as prominent editor of influential photographic magazines. (One such discovery was a young man named Nobuyoshi Araki.) Despite being well regarded as an editor, Kuwabara never gave up his snapshot approach to photography, and kept true to his open, wandering eye until the end. Both men, it is said, remained lifelong friends.

Their connection of both brotherhood and neighborhood makes for a fitting theme of the current exhibition at JCII Photo Salon in Hanzomon: “1930s Tokyo”. This exhibition brings together sixty-six silver gelatin prints of photographs taken at that time.

As a longtime Kuwabara fan, I had seen many of the pictures in books and at his major retrospective at the Setagaya Museum several years ago. Still, it's always nice to enjoy opportunities like these to see things up close. There are details in prints which cannot be expressed fully in books. Likewise, facing a wall of large pictures is very different than flipping through pages on your lap. This difference is worth the effort to visit an exhibition for.

Hamaya’s work here is more of a taxonomy of sorts- various things seen straightly, cleanly. His details of shop signs would be of as much interest to a historian as they would an art director working on an NHK pre-war period drama. Kuwabara's brilliant images, however, appeal to lovers of photography or poetry. His frames are responses to a compulsion to frame and keep a moment.

If, for example, Hamaya photographs a street stall vendor, we see accurately how such a man would have dressed and can infer as to what his job entailed. Kuwabara on the other hand, photographed the phenomena of street stalls- not the simply appearance of individuals, but the parts they played in the bustle of the stage that was Asakusa’s streets.

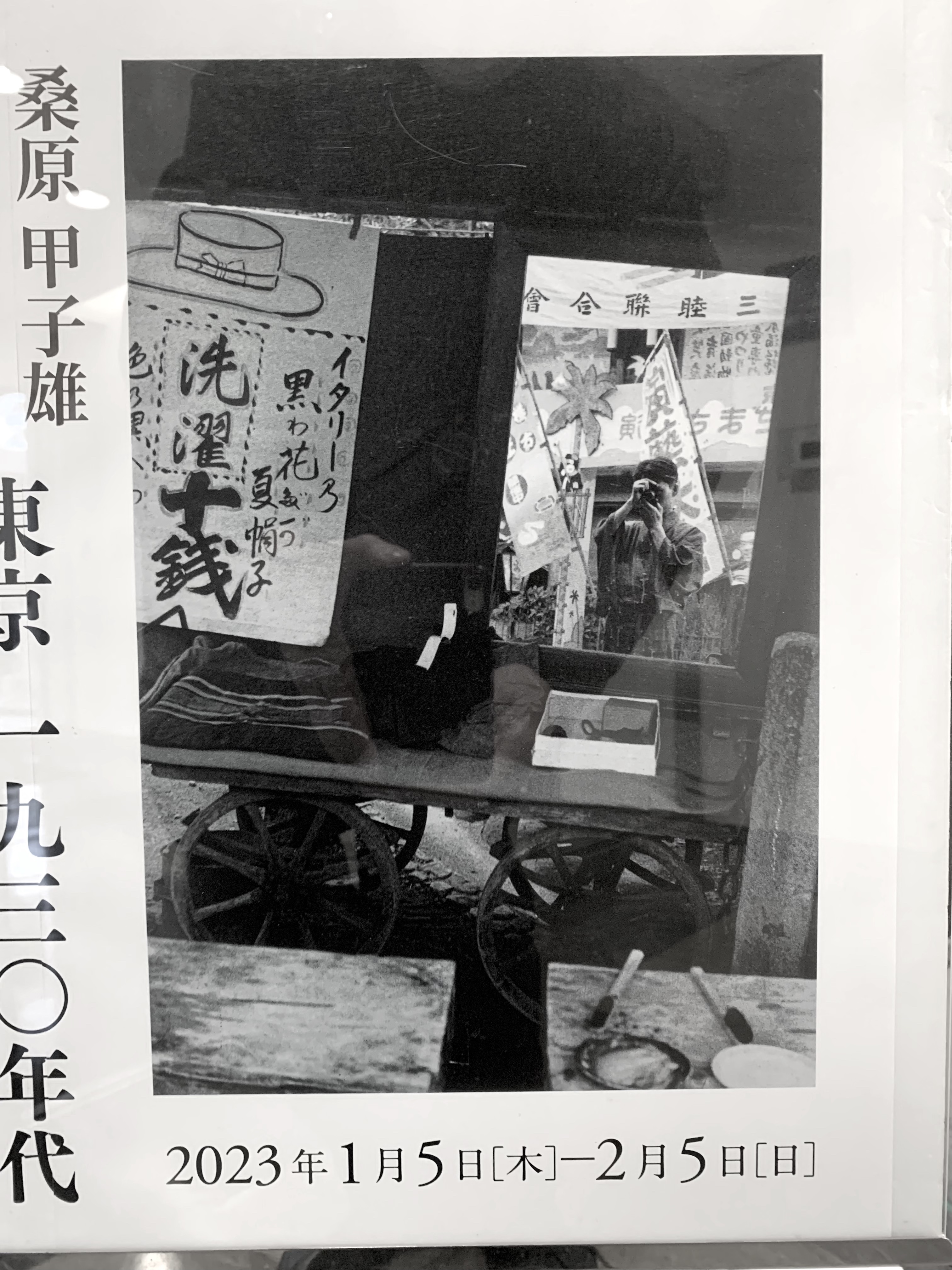

This difference in approach can be seen in the reflective self-portraits used for the show’s promotional poster: Hamaya frames himself with clarity and impact. With both hands firmly grasping his camera, he centers himself, matching his camera’s framelines with the actual frame of a mirror. His lens pointed exactly at what he wants to say. (He’s got a great hat, too.)

Yet, in his picture, Kuwabara emerges off-center from a slight distance out from a collage of multi-layered surfaces and objects. He’s less making a picture than he is taking one.

Personally, in Hamaya’s work I see a man using a lens to make a point- or an image.

In Kuwabara’s, I feel a shared sense of fascination for what a camera can reveal from the spontaneity of world. Such a feeling is part of everyone’s early experiences with photography- how rare and precious it was for Kuwabara to maintain this sense throughout his entire life.

“1930s Tokyo” is up at JCII Photo Salon in Hanzomon until Feb.5.

A small catalog featuring every exhibited image is available in the gallery shop. (1000 yen).

激動の1930年代後半、東京・下谷区(現:台東区)に住む二人の青年、桑原甲子雄と濱谷浩は、街を歩きながら好きなように写真を撮っていました。当時、濱谷さんはすでにフリーランスの写真家として活動していましたが、2歳年上の桑原さんは家族で質屋を営んでおり、写真撮影に必要な資金を調達していたそうです(当時のライカは家を買うのと同じくらいの値段だったと言われています)。

戦後、二人はそれぞれ写真関係のキャリアを形成していきます。

濱谷さんはフォト・ジャーナリストとして活躍し、1960年には日本人として初めてマグナム・フォトに入社できました。日本の山村文化や民俗をテーマにした作品は、日本の写真史に欠かすことのできないものです。

桑原さんの写真への関心は、有力な写真雑誌の編集者として、新人の発掘と奨励に移っていったのだと思われます。編集者として評価されながらも、桑原さんはスナップショット的な写真表現を捨てず、最後まで自由で、さまよえるような眼差しを持ち続けました。

二人は生涯の友であったと言われています。

2023年2月5日まで、半蔵門にあるJCIIフォトサロンで開催中の展覧会「東京1930年代」は、兄弟愛と近所付き合いをテーマにしています。 この展覧会では、当時撮影された写真66点の銀塩プリントが展示されています。

昔から私は桑原さんのファンとして、写真集や数年前に世田谷美術館で開催された大回顧展などで多くの写真を見ていましたが、こうして間近で見ることができるのは嬉しいことです。オリジナルプリントには、本では表現しきれないディテールがあります。また、壁一面の大きなプリントを前にするのと、膝の上でページをめくるのとでは、まったく違うのです。この違いは、わざわざ展覧会に足を運ぶ価値があると思います。

濱谷さんの作品はある種の分類学であり、様々なものをまっすぐ、はっきり見ることができます。店の看板のディテールは、歴史家にとっても、戦争を描くテレビドラマのアートディレクターにとっても、興味深いものでしょう。

一方で、桑原さんの鮮やかな写真は、文学や詩を愛する人たちにも訴えかける気がします。彼のフレームは、一瞬を切り取り、残すという衝動に応えています。

例えば、濱谷さんが屋台の人物を撮った場合、その人がどんな格好をしていたのか、どんな仕事をしていたのかということが正確に理解できます。一方、桑原さんは屋台という現象を、単に個人の姿ではなく、浅草の街という舞台の賑わいの中で、どのような役割を担っていたかを撮影しているのです。

二人の写真家の作品はそれぞれ素晴らしいですが、濱谷さんは「モノ」を、桑原さんは「コト」を撮られたのだと思います。

このアプローチの違いは、本展覧会のポスターに使用された、反射的な自画像写真に見ることができます。

濱谷さんの写真は、明瞭かつインパクトのあるフレーミングで自分自身を表現しています。両手でしっかりとカメラを握り、鏡のフレームに自分のフレームラインを合わせて、中心を定めています。レンズは彼が言いたいことにしっかりと向けられています。帽子も素敵。

桑原さんの写真は、幾重にも重なった表面や物体のコラージュのようなところから少し離れて、中心を外れて浮かび上がっています。この微妙な違いに、なにかがあるような気がします。

個人的に感じる話ですが、濱谷さんの作品には、レンズを使い、意識してイメージを作る欲望を感じます。

桑原さんの作品は、カメラが見せる世界の、少し不思議な姿に魅せられたという喜びを感じさせます。このような感覚は、誰もが写真に接する初期段階からもっているものですが、桑原さんが生涯にわたってもち続けたということは、稀有で貴重なことであったと思います。

「1930年代の東京」はJCIIフォトサロンで、2月5日まで開催されています。ぜひ見に行ってください。

また、ギャラリーショップでは、展示された全画像を収録したカタログを販売しています。1000円です。

桑原 甲子雄・濱谷 浩 作品展

「東京 1930年代」

2023年1月5日(木)〜2月5日(日)

JCIIフォトサロン

https://www.jcii-cameramuseum.jp/photosalon/2022/11/15/32522/

Vol.43 Azamino Photo Annual 2026 Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino 20th Anniversary Exhibition : Mr. Naylor’s Wunderkammer あざみ野フォト・アニュアル2026 開館20周年記念 横浜市所蔵カメラ・写真コレクション展「Mr.ネイラーの驚異の部屋」

2026/02/06

Vol.43 Azamino Photo Annual 2026 Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino 20th Anniversary Exhibition : Mr. Naylor’s Wunderkammer あざみ野フォト・アニュアル2026 開館20周年記念 横浜市所蔵カメラ・写真コレクション展「Mr.ネイラーの驚異の部屋」

2026/02/06

Vol.42 Werner Bischof at Leica Gallery Tokyo, Omotesando and Kyoto ワーナー・ビショフ写真展(ライカギャラリー東京、表参道、京都)

2026/01/31

Vol.42 Werner Bischof at Leica Gallery Tokyo, Omotesando and Kyoto ワーナー・ビショフ写真展(ライカギャラリー東京、表参道、京都)

2026/01/31

Vol.41 中嶋琉平|Ryuhei Nakashima「Asia, New York, and Tokyo」、高地二郎|Jiro Kochi「GINZA: Through the eye of a Salaryman 1950-1990」

2025/11/08

Vol.41 中嶋琉平|Ryuhei Nakashima「Asia, New York, and Tokyo」、高地二郎|Jiro Kochi「GINZA: Through the eye of a Salaryman 1950-1990」

2025/11/08

PCT Membersは、Photo & Culture, Tokyoのウェブ会員制度です。

ご登録いただくと、最新の記事更新情報・ニュースをメールマガジンでお届け、また会員限定の読者プレゼントなども実施します。

今後はさらにサービスの拡充をはかり、より魅力的でお得な内容をご提供していく予定です。

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け 書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント

書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント