コラム

落合憲弘

John Sypal

タカザワケンジ

なぎら健壱

The previous stop on my Tokyo Photobook Tour was TOKYO 1985 (https://photoandculture-tokyo.com/contents.php?i=832) , the debut photobook by Shoshi Okamoto. Published in 2019 by Sokyusha, this book collected photos of Tokyo he took as a young man in the mid 1980s as a student of Daido Moriyama and Masahisa Fukase at Tokyo Photographic College (Currently School of Visual Arts). Unable to begin a career in photography, these pictures, with perhaps a sense of resignation, were placed in a closet while he got on with the rest of his life. The afterword of TOKYO 1985 explains how he rediscovered his student work while cleaning up the house he then shared with his Alzheimic mother. He considers the publication of this collection- his debut photobook- as his “graduation project, 35 years in the making”.

While I was familiar with TOKYO 1985 and intrigued by both his photographs and story, I did not expect that he would publish two more photobooks of contemporary images so soon- nor could anyone have expected that they would so neatly pick up with where his student eyes had left off.

These books, Tokyo Summer 2020 (published 2021) and Everyday Tokyo 2021 (published 2022), are fascinating in how they act as waypoints for not only Okamoto’s own ongoing approach to the world but also as evidence of ongoing change of the city and people of Tokyo.

The closing of TOKYO 1985 begins with a short piece written by Daido Moriyama.

In it, the former teacher recalls how Okamoto was a “pale, usually wordless student” with a reticent, sharp stare. While I’ve yet to meet Okamoto myself, this characterization, coupled with Okamoto’s own somewhat glum review of his life in his afterword offers context for the temperamental, consistent sense of distance in his photographs. Rather than a street photographer who enlivens and is enlivened by close interaction on the streets, Okamoto remains an observer, and never a participant.

I don’t know if Okamoto photographed much between 1985 and 2020, but, as I have said, his recent work, taken 35 years after leaving photo school, uncannily retains its sense of distance and clarity. His eye and camera work remain so steady that you could shuffle a pile of 80’s prints with those from 2020 or 2021 and nothing would, aside from technological updates (car design, smartphone saturation) feel amiss.

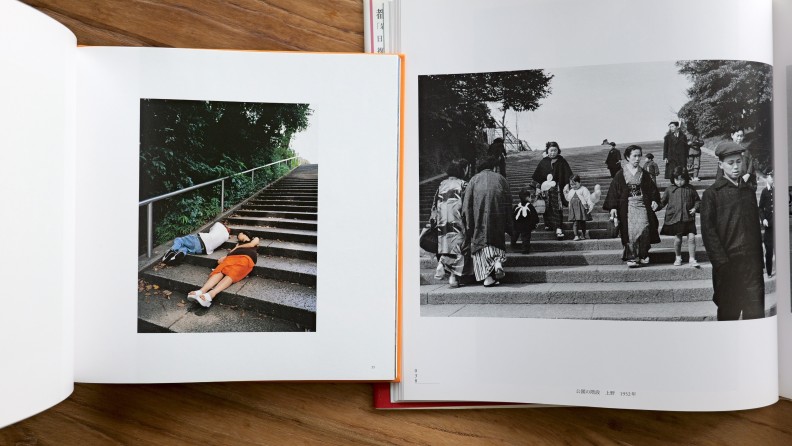

Looking through his 2020 & 2021 books, one will notice instances of wit, and even humor that are rare in his 1980s pictures. It feels like Okamoto is enjoying this rediscovery of photography.

On one page, a sanitation worker hops a road barrier, and on another, a child, immediately after a solo kick scooter wreck, lies flat in the street, caught with his leg still in the air. These things themselves aren’t particularly “funny” (especially if you’re that poor kid) but, included in amongst other pictures that have a more detached, calm approach to the city’s streets, add a bit of spark to the overall experience.

Of course, one thing you might remember about the summer of 2020 & everyday in 2021 was (is) the coronavirus pandemic.

In Japan, the government refrained from the sort of enforced, restrictive lockdowns that other countries implemented yet its suggestions / requests to prevent the spread of infection were adopted by companies, institutions, and individuals alike.

However, “The Pandemic” is not the subject of Tokyo Summer 2020 or Everyday Tokyo 2021. The subject of the photographs remains Okamoto’s line and scope of sight- the world immediately in front of his lens, on Tokyo’s backstreets.

Unlike say, a tsunami or earthquake, a world-changing viral emergency is too large for any single photographer to conquer with a camera. In Tokyo, life more or less plodded on and Okamoto continued his walks. The pictures he made never presume to dramatically illustrate the city in the midst of crisis- yet reverberations of the pandemic inevitably and tangentially appear in the photographs.

In Japan in 2020 & 2021, (and daily in to our current 2022) masked figures exist apart from each other, often with heads tilted down towards the glass-rectangle worlds in their palms. In others, people continue their work or leisure- but with a dry gap measured in meters.

The distance he’s captured is both social and mental- without pretension or drama his work has the feel of now. If we can agree that the streets were more jovial and rambunctious in the late Showa period, I can’t help but feel that society itself has caught up to the intrinsic, personal sense distance reflected in his pictures made forty years ago.

In addition to ideas about society, Tokyo Summer 2020 & Everyday Tokyo 2021 also invite visual comparisons with Tokyo of 1985.

Here I’m thinking about surfaces- the architecture, the physical changes undergone along the streets. Okamoto remains drawn to the maze of backstreets that make up the bulk of the city and Tokyo, being a collection of mashed-together, ever-reconditioned villages, provides inexhaustible paths which to take a camera. Like so much of the city (particularly in the past eight years) buildings along the once-bustling neighborhood shotengai shopping streets have been replaced with blank looking, plastic and practical houses or apartments.

The streets are emptier- surely an effect of the pandemic- but they’re now flatter, too. There are fewer gaudy signs and more order. Open-fronted locally-run shops disappear to be replaced by convenience stores or new apartments with entrances of hard glass and security cameras.

Corporate parks too, appear in Okamoto’s books. Their street levels landscaping is vast in scale while being more secure, and colder. Humans in these places are reduced in size by the design and perhaps in spirit by its planned, gigantic hollowness.

And yet, Okamoto’s pictures remain non-judgmental. Nor are they particularly sentimental- they’re not laments of a vanishing past. A photo walk is, for the photographer, if not simply the best a way to forget about troubles, a way of focusing on the absolute, immediate present. Okamoto’s pictures then, with their clarity and distance, are byproducts of what it means to wander and look, and, for oneself alone, take a photograph.

We are lucky that he’s felt they are worthy of sharing annually- and I’m looking forward to experiencing he sees 2022 and beyond.

前回のTokyo Photobook Tourは、岡本正史さんのデビュー写真集『Tokyo 1985』でした。2019年に蒼穹舎から刊行された『TOKYO 1985』は、東京写真専門学校(現ビジュアルアーツ専門学校)で森山大道氏や深瀬昌久氏に師事した1980年代半ば、青年期に撮影した東京の写真を集めたものです。卒業後、写真の道へと進むことができず、諦めの境地だったのか、これらの写真は押入れにしまわれたまま、その後の人生を歩むことになります。『TOKYO 1985』のあとがきには、アルツハイマー病の母親と同居することになった家の片づけをしているときに学生時代の作品を再発見したことが書かれています。 この写真集の出版を、彼は「35年越しの卒業制作」と位置づけているのです。

『TOKYO 1985』の写真と物語に興味をもっていたのですが、2021年に蒼穹舎へ行って彼の二作目の写真集『Tokyo Summer 2020』を見た時、彼がこんなにも早く現代のイメージの写真集も出すとは、誰も思っていなかったのではないかと驚きました。すごい。

写真集『Tokyo Summer 2020』(2021年刊行)と『Everyday Tokyo 2021』(2022年刊行)は、岡本さん自身の世界へのアプローチだけではなく、東京の都市と人々の現在進行形の変化を示す中継点として機能しているところが魅力的です。

『TOKYO 1985』のエンディングは、森山大道氏が書いた短い文章で始まります。森山氏は、岡本さんは「青白く、普段は言葉を発しない生徒」で、寡黙で鋭いまなざしを持っていたと回想しています。

私はまだ岡本さんと会ったことはありませんが、この人物像と、あとがきに書かれている岡本さん自身のやや暗い人生の振り返りが、彼の写真に見られる気質的で一貫した距離感の背景を物語っているように感じます。 岡本さんは、街角での交流によって活気づく街頭写真家ではなく、あくまでも観察者であり、決して参加者ではないのです。

1985年から2020年の間に岡本さんがどのように写真を撮っていたのかは知りませんが、写真学校を卒業して35年経った最近の作品には、不思議なほどに距離感や透明感が続いています。 彼の眼とカメラワークは非常に安定しており、80年代のプリントの山と2020年、2021年のプリントをシャッフルしても、テクノロジーのアップデート(車のデザイン、スマートフォンの飽和)を除けば、何も違和感を感じません。

2020年、2021年の写真集を見ると、1980年代の写真にはないウィットやユーモアがあることに気づくでしょう。岡本さんは写真の再発見を楽しんでいるように感じられます。あるページでは、自衛隊員が道路のバリアを飛び越え、別のページではキックスクーターの単独事故の直後、子供が足を宙に浮かせたまま道路に横たわっている。それ自体は特に「面白い」わけではないのですが、街の通りをより冷静にとらえた他の写真に混ざると、全体の体験にちょっとした輝きを与えているのです。

2020年といえば、新型コロナウイルスの大流行が記憶に新しいと思います。日本では、諸外国のような強制的な閉鎖は行われませんでしたが、感染拡大を防ぐための提案や要望が、企業や団体、個人を問わず採用されました。

津波や地震の災害と違って、世界を変えるようなウイルスによる緊急事態は、一人のカメラマンがカメラで制圧するには大きすぎるのではないでしょうか。

パンデミックは『Tokyo Summer 2020』や『Everyday Tokyo 2021』の主題ではありません。 写真の対象は、岡本さんのレンズの前に広がる世界、東京の路地裏であり、彼の視線と視野です。東京ではほぼ日常生活が営まれ、岡本さんは散歩を続けていました。彼の写真は、危機的状況にある東京を劇的に表現するものではありませんが、パンデミックの余波は、必然的に写真に現れています。

2020年、2021年の日本では(そして2022年の現在も)、マスク姿の人々が互いに離れて存在し、しばしば手のひらの中のガラスの四角い世界に向かって頭を傾けている。他の場所では、人々は仕事やレジャーを続けていますが、メートル単位で計測される乾いた隙間があります。

その距離感は社会的、精神的なものであり、気負いもなく、ドラマもなく、今を感じることができます。昭和の終わり頃の街はもっと陽気で賑やかだったのだとすれば、40年前の彼の写真に映し出された本質的でパーソナルな距離感に、社会そのものが追いついてきたと感じずにはいられないのです。

『Tokyo Summer 2020』と『Tokyo Everyday 2021』は、社会に対する考え方だけでなく、1985年当時の東京との視覚的な比較も可能にしています。

私はここで、建築物や街路の物理的な変化など、表面について考えているのです。岡本さんは、東京の路地裏に惹かれ続けています。東京は、混ざり合い、常に再生されている村の集合体であり、カメラを向けるための道を無尽蔵に提供してくれます。 この街の多くがそうであるように(特にこの8年間は)かつて賑やかだった商店街の建物は、プラスチックっぽくて実用的な、何もない家やアパートに置き換えられています。

街は空っぽになり、パンデミックの影響でしょうが、平坦になりました。派手な看板も少なくなり、整然としています。 地元密着型のオープンな店は姿を消し、コンビニエンスストアや新しいマンションに取って代わられ、入り口は硬質ガラスで、監視カメラが設置されています。

岡本さんの本には、企業団地も登場します。街角の景観は広大なスケールで、より安全で、より冷たくなっています。このような場所にいる人間は、デザインによって小さくなり、おそらく精神的にも、その計画された巨大な空洞によって小さくなっているのです。

しかし岡本さんの写真は、決して批判的なものではありません。特にセンチメンタリズムでもなく、消えゆく過去を嘆いているわけでもありません。写真散歩は、写真家にとって、煩悩を忘れ、絶対的な現在に集中するための最良の方法です。 岡本さんの写真は、その透明感と距離感から、歩き回ること、見ること、そして自分一人のために写真を撮ることの副産物です。

岡本さんが毎年、この写真を公開するに値すると感じたことは幸運であり、今後も彼の写真集を楽しみにしています。

- 岡本正史『Tokyo Summer 2020』

- 蒼穹舎・2021年5月・3,520円(税込)

A4変型・モノクロ64ページ・作品59点・上製本・300部

編集:大田通貴

装幀:塚本明彦/赤川延美(タイプセッティング)

蒼穹舎- 2020の春、認知症の母が老人ホームに入りました。

夏になって、東京の大きな地図をリビングの壁に貼りました。

そうしてカメラを連れて訪れたところに、印をつけていきました。

(あとがきより一部抜粋)

- 岡本正史『Everyday Tokyo 2021』

- 蒼穹舎・2022年5月・3,520円(税込)

- A4変型・モノクロ64ページ・作品58点・上製本・300部

- 編集:大田通貴

- 装幀:塚本明彦/赤川延美(タイプセッティング)

- 蒼穹舎

26 Duets? Duels? Near-overlaps of time and Space across Tokyo. 東京の時間と空間が重なり合う写真集ツアー

2025/04/04

26 Duets? Duels? Near-overlaps of time and Space across Tokyo. 東京の時間と空間が重なり合う写真集ツアー

2025/04/04

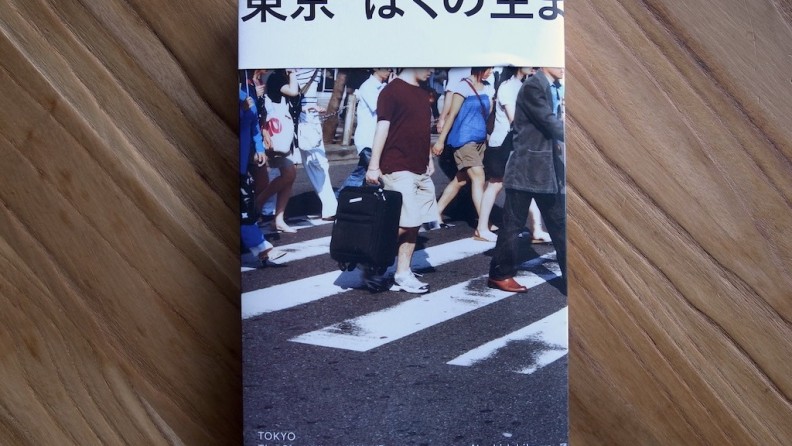

25 Naoki Ishikawa "TOKYO The City Where I Was Born" 石川直樹『東京 ぼくの生まれた街』

2024/01/05

25 Naoki Ishikawa "TOKYO The City Where I Was Born" 石川直樹『東京 ぼくの生まれた街』

2024/01/05

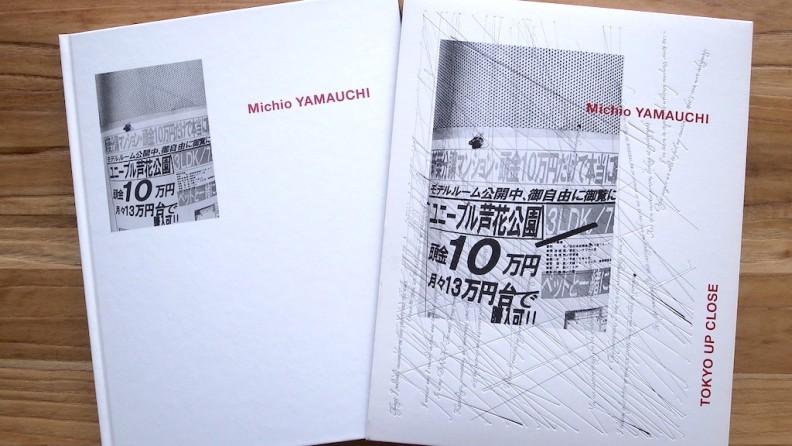

24 山内道雄 Michio Yamauchi『TOKYO UP CLOSE』

2023/10/20

24 山内道雄 Michio Yamauchi『TOKYO UP CLOSE』

2023/10/20

PCT Membersは、Photo & Culture, Tokyoのウェブ会員制度です。

ご登録いただくと、最新の記事更新情報・ニュースをメールマガジンでお届け、また会員限定の読者プレゼントなども実施します。

今後はさらにサービスの拡充をはかり、より魅力的でお得な内容をご提供していく予定です。

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け 書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント

書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント