コラム

落合憲弘

John Sypal

タカザワケンジ

なぎら健壱

In 1937, while Henri Cartier Bresson was running around Europe with his Leica, a son of a downtown pawn shop owner was doing the same thing in pre-war Tokyo.

This young man, Kineo Kuwabara (1913-2007), finding himself possessing that which all photographers benefit: skill, curiosity and- perhaps most importantly- financial stability from a successful family business, was allowed the opportunity to pursue amateur photography at a time in Japan when his Leica cost as much as a house. In this way he was able to spend the late thirties ambling about with his camera in and out of Tokyo’s downtown districts- the chaotic, painfully photogenic streets of pre-war Ueno, Asakusa and the dry, dusty slums of Arakawa, to name but a few.

After a stint as a photographer in Manchuria from 1940, his post-war years saw his reputation grow as a respected camera magazine editor. In the early 1970s he was “re-discovered” as a photographer by one of his own discoveries, a young Nobuyoshi Araki. Araki, smitten with Kuwabara’s pre war Tokyo shitamachi photos, was instrumental in the publication of Kuwabara’s first photo book, Showa Tokyo 11 (Shobunsha, 1974). Despite not having a solo exhibition until the age of 60, Kuwabara never stopped photographing his city, continuing his Tokyo walks with his prewar Leica (and later, Konica Hexar) into the 1990s. It was in 1993 when he and his “protege”Araki, held an exhibition together in 1993 titled Love You Tokyo at the Setagaya Art Museum. (The catalog of this show is an underrated masterpiece and is still quite common and affordable.)

Since the mid 70s, several fine collections of Kuwabara’s photographs have been published. Many of these, due to the nostalgic/historical aspects of his pictures, are less Fine Art Photobooks than they are practically printed and captioned and (thankfully) priced books for those curious about Japan’s recent past. The book I’d like to look at this week, 1995’s “Tokyo 1934-1993”, falls along those lines but surpasses all the rest of his in terms of quantity.

With an exclamation mark the book’s obi announces that a total of 736 images lie inside. That’s actually a little over 100 more pictures than there are pages. “Chunky” is a good adjective to describe this book- and one can add “adequate” in terms of its printing and maybe “90’s fat paperback” in terms of binding. I’ve found that a lot of similar 90’s Japanese softcover photobooks suffer from startling (and permanent!) cracking sounds the moment some pages are opened too far. While the stitching seems secure enough, expect used copies (or yours after an hour) to have a few lay-flat pages sprinkled within. While slightly affecting the look of the book (from the top down), if you're an optimist and not a white-gloved collector, it makes the reproductions somewhat easier to view and enjoy.

While many are printed two to a page, each picture is numbered and given a brief caption stating year and location, in English. (The afterword tells us that some pictures were captioned “no date” and “location unknown”, since Kuwabara never kept such info with his negatives.

There are several pages in the back of the book with longer notes- these, transcribed from in Kuwbara’s own words, offer some further context and anecdotes. Unfortunately these are in Japanese, only.)

So, yes, at over 600 pages, this book has a certain physical density but its temporal weight is even more interesting. Looking at some of his pictures in the mid 1930s, I can’t help but consider him to be a photographer of Edo. In his pictures we find people who seemed to have stepped out of a portal (or woodblock print) from two-hundred years earlier.

The particular 59 years of Tokyo this book collects contained such transformation it’s hard to believe that any one person could have lived through them- yet obviously millions did. And likewise, many took photos. Tokyo has never been lacking in visual documentation- it has got to be one of the most photographed cities ever- but rather than rote photo-illustration / photojournalism or the graphic dynamism of younger postwar photographers, the enduring charm of Kuwabara’s work lies in its nonchalant openness- that spirit of a satisfied, bemused amateur.

With his sense of curiosity and a straightforward approach, Kuwabara’s pictures reveal with such clarity not the extraordinary but a type of ordinary which time has, through ruin and rust and rebuilding and fuzzied memories, polished into nostalgia. Straightforward is, quite simply, more than enough. Whether 1937 or 1987, in his pictures people go about their days, passing by on the streets while children tend to their little worlds in back alleys under drying laundry. Signs (hand-painted- a photographer favorite) sit in the sun. Stall vendors sell their wares. Pre-war disaster drills and post-war photo club shoots aside, things are, overall, pretty normal. Very rarely is it in his pictures that things are actually happening.

By “things”, here I mean incidents or compositions which might be generally considered as out of the ordinary, or, having mentioned HCB earlier, Decisive.

Bresson might have brilliantly balanced his compositions on delicate suspensions (a foot over a puddle, a bicycle passing a hand railing) but Kuwabara, in a different way, made work I find just as precious- perhaps the glance of a girl on the street- or a nearly bare ankle briefly glimpsed from under a kimono.

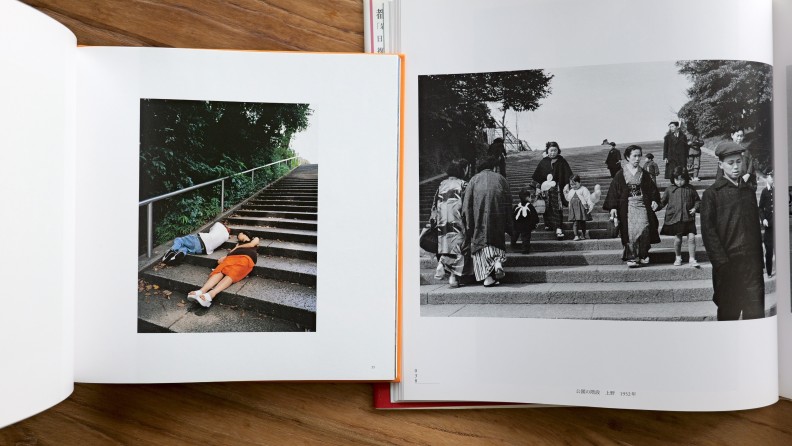

Kuwabara photographed the same areas of the city throughout his life creating, inevitably, a record of its changes. One of my personal interests in Kuwabara’s work connects to my hobby of rephotography. For several years now I have been locating spots in Tokyo where Kuwabara (and others) have made pictures. Much in Tokyo has changed in the past forty years- and hardly anything from the 1930s remains. But sometimes, glimpses of Kuwabara’s world remain.

Please allow me to end this column with a few “then & now” pictures based on the work of Kineo Kuwabara- and the generous amount of pictures from Tokyo 1934-1993.

1937年、アンリ・カルティエ=ブレッソンがライカを持ってヨーロッパを駆け回っていた頃、戦前の東京では下町の質屋の息子が同じようなことをしていた。

桑原甲子雄(1913-2007)はその時、写真家なら誰でも欲しい3つの貴重な品を持っていました。それはいいカメラ、好奇心、家業が順調で経済的に安定していたこと。当時ライカが家一軒分の値段だった日本で、桑原さんはアマチュア写真家として活動する機会を得ます。 戦前の上野、浅草、荒川の乾いた埃っぽい下町など、痛々しいほどフォトジェニックな東京の下町を30代後半はカメラを持ってぶらぶらと歩いていました。

1940年から満州で写真家として活動した後、戦後はカメラ雑誌の編集者として名声を高めました。 1970年代初頭、桑原さんは自身の発掘者である若き荒木経惟に写真家として「再発見」されます。戦前の東京下町の写真に魅せられた荒木さんは、桑原さんの戦前の写真集『昭和の東京11』(晶文社、1974年)の出版に尽力したそうです。60歳まで個展を開くことはありませんでしたが、桑原さんは街を撮ることをやめず、戦前のライカ(後にコニカヘキサー)を手にずっと東京散歩を続けたのです。1993年、"弟子 "の荒木さんと二人で世田谷美術館で展覧会「LOVE YOU TOKYO」を開催しました(この展覧会のカタログは過小評価されているように感じますが、傑作です。今でも手頃な価格で見つることができます)。

1970年代半ばから、桑原さんはいくつか立派な写真集を出版されています。その多くは、彼の写真のノスタルジックで歴史的な側面から、ファインアート写真集というよりも、日本の過去に興味をもつ人たちのために、実質的に印刷され、キャプションが付けられ、値段が付けられた本になっています。

さて、今週ご紹介する東京フォトブックは1995年の『東京 1934〜1993』です。

本の帯には「全736点!」と書かれています。これはページ数より100点も多いのです。 この本を形容するのに適した形容詞は「分厚い」であり、印刷に関しては「まぁ十分」、装丁に関しては「90年代の太いペーパーバック」かもしれません。装丁ですが、90年代の日本のソフトカバー写真集の多くは、ページを開きすぎた瞬間にびっくりするような「パキッ!」という割れ音に悩まされることがあります。縫製はしっかりしているように見えますが、中古の本には、平らなページがいくつか散らばっていることが予想されます。本の見た目(上から下へ)には若干の影響がありますが、もしあなたがコレクターではなく、楽観主義者であるなら楽しむことができると思いますよ。

1ページに2枚ずつ印刷されているページが多いのですが、各写真には番号が振られ、英語で年号と撮影地が書かれた簡単なキャプションが付けられています。あとがきによると桑原さんはネガにそのような情報を記してなかったので、いくつかの写真には「日付なし」「場所不明」というキャプションが付けられています。

600ページを超える本書は、ある種の物理的な密度もありますが、それ以上にその「時間的」な重みが面白いのだ。1930年代半ばの彼の写真を見ると、彼はまさに「江戸時代の写真家」だと思わざるを得ません。 彼の写真には、200年前のタイムスリップ(あるいは浮世絵)から飛び出してきたような人たちが写っている、素晴らしいです。

この本に収められている東京の59年間は、一人の人間が生きてきたとは思えないほどの変貌を遂げていることが見てとれます。そこには確かに何百万人もの人間が生きていて、そして同様に多くの人が写真を撮りました。しかし、桑原さんの作品の魅力は、戦後の若い写真家たちのようなフォト・イラストレーションやフォトジャーナリズム、グラフィック・ダイナミズムではなく、その淡々とした開放性で、つまり、満足し困惑するアマチュアの精神にあるのです。

桑原さんの好奇心と素直なアプローチは、非日常性ではなく、時間が廃墟や錆、再生、記憶の曖昧さを経て、ノスタルジーへと磨き上げた一種の日常を、鮮明に浮かび上がらせてくれます。 素直であること、それだけで十分なのです。1937年であれ1987年であれ、彼の写真の中では人々が日々を過ごし、通りを行き交い、子供たちは路地裏の洗濯物の下で小さな世界に入り込んでいる。写真家のお気に入りである手描きの看板が日なたに置かれている。屋台の売り子たち。戦前の防災訓練や戦後の写真部での撮影はともかく、全体としてはごく普通の風景。彼の写真には、実際に何かが起こっている「サムシング」はほとんどありません。

ここでいう「サムシング」とは、一般的には常識外れと思われる事件や構図、あるいは先ほどのブレッソンの話にも出てきた「決定的瞬間」のことです。

ブレッソンという例えを使えば、水たまりの上の足の止まり方。また、手すりを通過する自転車など、微妙なバランスで構成されていますが、桑原さんは別の意味で、道行く少女の視線や、着物の下からちらりと見える裸の足首など、貴重な作品を作っています。何もないからこそ、何かがぜったいあるのです。

桑原さんは東京の下町などを撮影し続け、必然的に街の変化を記録することになりました。桑原作品への個人的な興味は、私の趣味であるリー・フォトグラフィ(Re Photography)と結びついています。

ここ数年、私は桑原さんをはじめさまざまな写真家が撮影した東京のスポットを探し、再撮影をしています。東京は40年で街が大きく変わり、1930年代のものはほとんど残っていません。 しかし、頑張れば、時折、桑原ワールドが垣間見えます。

Ueno Station, 1936 / 2018

桑原甲子雄の作品に基づく「今と昔」の写真とこのコラムを終えることにします。

- 桑原甲子雄

- 『東京 1934〜1993(フォト・ミュゼ)』

- 新潮社 ・1995年・629ページ

26 Duets? Duels? Near-overlaps of time and Space across Tokyo. 東京の時間と空間が重なり合う写真集ツアー

2025/04/04

26 Duets? Duels? Near-overlaps of time and Space across Tokyo. 東京の時間と空間が重なり合う写真集ツアー

2025/04/04

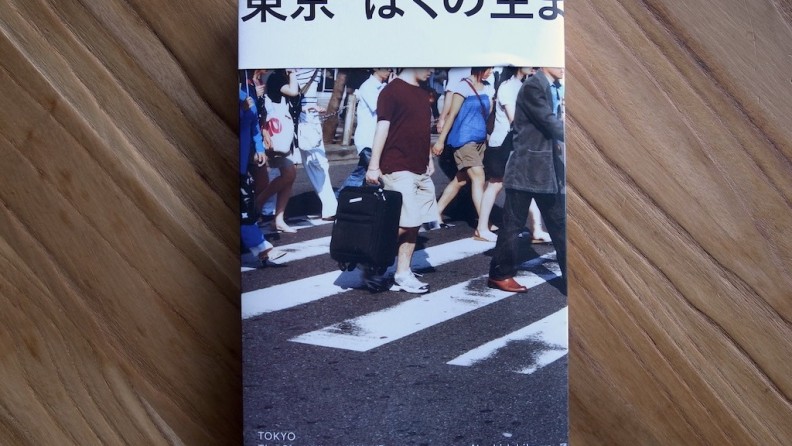

25 Naoki Ishikawa "TOKYO The City Where I Was Born" 石川直樹『東京 ぼくの生まれた街』

2024/01/05

25 Naoki Ishikawa "TOKYO The City Where I Was Born" 石川直樹『東京 ぼくの生まれた街』

2024/01/05

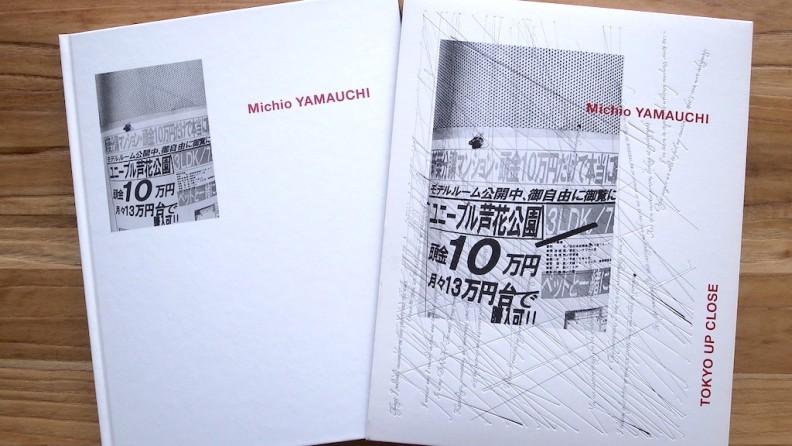

24 山内道雄 Michio Yamauchi『TOKYO UP CLOSE』

2023/10/20

24 山内道雄 Michio Yamauchi『TOKYO UP CLOSE』

2023/10/20

PCT Membersは、Photo & Culture, Tokyoのウェブ会員制度です。

ご登録いただくと、最新の記事更新情報・ニュースをメールマガジンでお届け、また会員限定の読者プレゼントなども実施します。

今後はさらにサービスの拡充をはかり、より魅力的でお得な内容をご提供していく予定です。

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け

「Photo & Culture, Tokyo」最新の更新情報や、ニュースなどをお届けメールマガジンのお届け 書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント

書籍、写真グッズなど会員限定の読者プレゼントを実施会員限定プレゼント